It’s been a decade since I made the accidental discovery which caused me to rise from my chair, walk away from my computer, and seriously consider whether I had lost my mind.

In preparing a booklet about the life of Thomas Lovewell, I had begun searching for historical photos that were in the public domain, to help illustrate various stages of his fascinating life. To accompany the story of his first footloose adventure into the Far West in 1859, I went to the Library of Congress website, typed “Pikes Peak or Bust,” and hit return. There wasn’t much. However, one photograph seemed to be a possible candidate, so I downloaded the eight megabyte tiff file provided by the Denver Public Library and had a look.

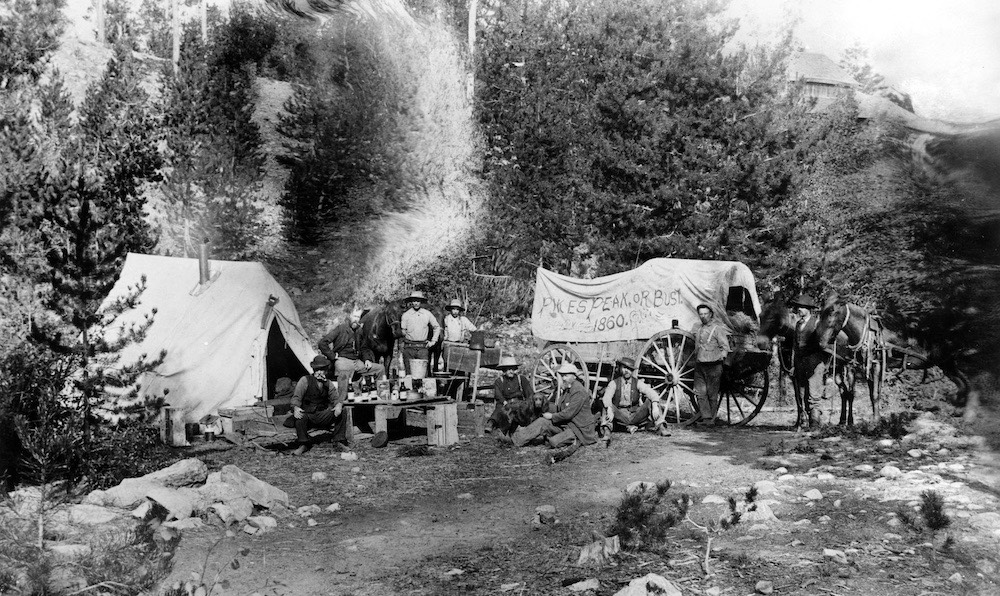

Though marred, perhaps by an errant splash of darkroom chemicals, the photo was incredibly vivid and modern-looking, like an impromptu shot staged during a lunch break on the set of Wagon Train. However, I would quickly come to realize that what I was examining was not some later historical re-creation, but a very early example of outdoor wet-plate photography. The men arranged for the occasion were the real deal, actual pioneers hell-bent on finding gold on the slopes of Pikes Peak, circa 1859.

When a tall figure in a white blouse on the left side of the scene caught my eye, I had to chuckle. I was looking for something to accompany the story of Thomas Lovewell leaving his family behind in Iowa while he went west looking for gold, and here was a man who may have been doing the exact same thing, and who actually looked something like the subject of my tale.

I clicked the zoom button to zero in even tighter, expecting to reveal some feature that would distinguish this stranger from the man I was writing about. It never happened. The closer I got, the more it looked just like him. Finally I had magnified the image past the limits of photographic resolution and compression-pixellation, until the face was a blocky patch of fuzz that was somehow still staring at me intensely, straining to be recognized. That’s when I got up and tried to shake off the growing impulse to believe it could possibly be him.

I read everything I could find about the main characters involved in the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, and about the family of the man who had donated this damaged treasure to the library. Then I set about determining who many of the people in the photograph must be and why it may have been staged in the first place.

At the extreme left side of the photo, the hosts of the gathering, “California Abe” Walrod and Daniel Chessman Oakes, maintain a hospitality bar for their guests. While waiting for his new house to be completed in Denver City, Oakes is described in contemporary accounts as sharing a tent with Walrod beside a mill stream. Perhaps not coincidentally, the camera has captured a small waterfall cascading from atop the right side of the hill behind the men.

Oakes had appended a short travel guide to a pamphlet called “History of the Gold Discoveries on the South Platte River.” Before making his latest trip west from his home in Pacific City, Iowa, he ordered a fresh batch of copies to sell along the way. The printer would never be reimbursed by Oakes, who would return to Iowa only long enough to gather up his family and begin hauling them all to Denver. The cover of the wagon in the photograph has been painted with an advertisement for the guidebook, with the date moved ahead to 1860, as though the famous 1858 pamphlet has seen an update. It is difficult to make out the entire message because it appears to have been painted in an assortment of colors, some of which were too light to stand out against the wagon sheet when rendered in shades of gray. Some misspellings may also be involved, but the gist seems to be “Pikes Peak or Bust - Chess Oakes’ 1860 Guide.”

Oakes had made the journey several times in quick succession. One of the companies of hopeful visitors making the trip in tandem with Oakes that spring was referred to in a trail diary as “Williams' from Michigan." Although I’ve found no record that miner John Henry Williams followed the trail to Pikes Peak in 1859, apparently he did. There he is, seated on the ground wearing an oversized white hat in the photograph above, and elsewhere on this site. Williams’ grandson, a well-known Colorado lawman was the benefactor who donated the widely-reprinted picture to the Denver Public Library. The two gentlemen nearby wearing bucket hats might be family members recently arrived from Cornwall, John Henry’s father Collan and his brother Liam.

If the visitors are indeed hopeful adventurers newly-arrived at Pikes Peak, then the gathering in the pines probably took place in Late June of 1859. Oakes is wearing a black armband in the photograph, possibly a token of mourning for his wife’s late mother, who had died eleven months earlier.

It’s estimated that 100,000 pioneers headed for Pikes Peak during the 1859 gold rush. Even if only 20,000 went the whole distance, the odds that the man I was writing about would turn up in what is essentially the poster for the event, seemed almost infinitesimal. Mathematical improbability was the only stumbling block in my mind to declaring it very likely to contain the earliest image of Thomas Lovewell. But there was also the fuzziness of the photo, which had to introduce a measure of uncertainty.

Phil Thornton dropped into the Denver Public Library a few years back to get a closer look, but even the resolving power of 21st century lenses won’t necessary sharpen soft images. However, artificial intelligence might.

A few days ago I watched a YouTube video about a free online service that will, among other things, use A.I. to increase the clarity of a fuzzy photograph by a factor of four, calculating the brightness of adjacent pixels to determine where the actual boundaries of a subject’s features lie.

At no cost to me, it was certainly worth an experiment. I went back to the original tiff image downloaded in 2012, cropped it down to the part with the two men whom I believed might be Thomas and Solomon Lovewell, and dropped it on the server. The result was available for downloading within minutes.

If my eyes have deceived me into thinking the picture contains the image of Thomas Lovewell, I’m not alone. The A.I. seems to agree with me. The shaggy forelock, reflexive scowl, neatly-trimmed mustache, prominent cheekbones and distinctly wide nasolabial folds (laugh lines) - all the trademarks are in place and clearly defined as never before.

I’ve added a black and white version of the photo from the website banner, for comparing an image of young Thomas Lovewell with his portrait taken 34 years later, following his reunion with the daughter he left behind in 1859 on a fruitless trip to Pikes Peak.