Everyone who knows Gordon Winbigler’s story can probably recite two facts about his death in 1868: he was killed because he stopped to retrieve his hat and he was buried in a box made of puncheons. Since some history books go further in specifying that Gordon’s beloved headgear was a plug hat, we probably need to define two terms at the outset.

Puncheons were logs sawed in half lengthwise, with at least one side smoothed, the other sometimes left rough and rounded. The lumber used as a coffin for Gordon in mid-August, 1868, was pried up from the floor of a cabin owned by Daniel N. Davis, the brother of Orel Jane Lovewell, who were both present when Gordon Winbigler was shot and stabbed. While only one side of a floor needs to look presentable, using puncheons for a coffin meant that either the coffin looked ungainly or Gordon looked uncomfortable in it. As for that plug hat, the term denoted a stiff hat with a narrow brim, such as a bowler or top hat.

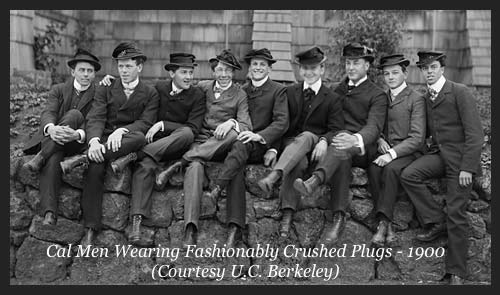

Which style Gordon’s hat resembled we can only guess, but we are probably meant to understand that his hat was distinctive, not a military cap from his days in the U. S. Cavalry or something suitable for punching cattle on the Plains of Kansas. Instead it was a hat that practically dared people to call the wearer a dandy. Such a man did not deserve to spend eternity reclining on the knobby side of a row of puncheons.

The killing of Gordon Winbigler came up while I was searching for evidence that Thomas Lovewell either was or wasn’t in Kansas in 1901. Finding nothing to convince me that he was, I began to be convinced that he had returned to Alaska for one more try at the gold fields of the Far North before turning his attentions to the hills of Wyoming the following year.* What my search did turn up was an address on local history prepared by his wife, Orel Jane Lovewell, and delivered by Mrs. J. R. Fullen at the Old Settlers’ Picnic August 29, 1901.

Orel Jane touched on other episodes of frontier violence such as the Jewell County Massacre of 1867, providing a few details not previously known, for instance, the fact she had visited with Mary Ward two days before the young woman was taken captive by a raiding party, never to return. Amusingly, she refers to one of the victims, Mrs. Setzer’s boarder Erastus Bartlett as “Mr. Bachelor.” Hardly anyone ever remembered Bartlett’s name, sometimes calling him “Mr. Rice” or omitting any mention of him at all. We have to wonder whether Orel Jane penciled in the name “Mr. Bachelor,” intending to look up the actual name later, or if that was what Mary Ward had called him with a twinkle in her eye, raising an eyebrow at the notion of the estranged wife of Josiah Setzer sharing a cabin with an unattached young veteran.

Turning to the incident in the hay meadows in 1868, Orel Jane did little to set the scene, but probably felt she didn’t need to. According to Isaac Savage’s updated history of the county, which had been published a few months before the Old Settlers’ Picnic, a group of about two dozen settlers, including women and children, worked in the hay meadows on the east side of the Republican River, near a fort made of eight log cabins arranged in a square. When Indians suddenly appeared, everyone in the field made a frantic dash for the fort. Gordon Winbigler was part of a group of four separated from the others. Among the three in a hay wagon was Orel Jane’s nephew David Davis.

The men were making hay and hauling logs when a band of “braves” - fifty or more - came from the timber and advanced near the hay field and then started for the camp, but one brave boy stopped to get horses and mounting one of them he started for the camp when he stopped to get his hat which he had dropped. This hesitation probably cost him his life for the foremost Indian shot him. He called to young Davis: “Go on, I am shot.” He had no firearms and the same Indian who had shot him speared him through the heart. This lad’s name was Gorden Windbingler.

He was brought to camp and the Indians went back after they were shot at several times. Gorden was a widow’s only son who had come from Ohio to make a home for his mother. He was an honest, sober young man. This was in August 1868. No doubt his mother has met him ere this, in the home where the Divine Healer dwells. But, may I ask the Old Settlers “Is it right to leave him in a lone, rough puncheon box?” What was the best and only way that he could be buried at that time. Now, I hope you will see to it that he is laid away in a cemetery.

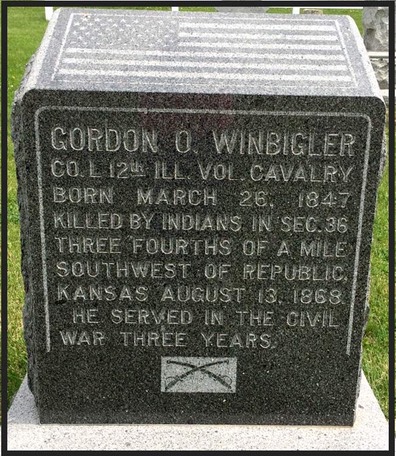

Although the 21-year-old evidently struck Orel Jane as a mere boy, Gordon Orlando Winbigler had enlisted in the U. S. Army at the age of 16 as a private in 1863, and was a full sergeant by the time he was mustered out at Houston, Texas, in 1866. Not that it matters, he had not come from Ohio but Illinois, where his parents and most of his siblings are buried.

It is true that Gordon’s mother, Amanda Rachel Gordon Winbigler, was a widow whose husband Elias had died in 1864 at the age of 48, although Gordon was not her only son. In fact, two of his brothers and two sisters were still living when Orel Jane’s remarks were delivered at the Old Settlers’ Picnic in 1901. In his 1901 history Savage, who consistently misspells Winbigler’s name as “Windbigler” (Orel Jane went him one better, seeing his “d” and raising him an extra “n"), may have been making a hopeful prediction with his statement,

Windbigler’s remains were some time afterwards disinterred and removed to his old home in Indiana.

Gordon’s final resting place is distinctive for being scattered among three possible locations on Findagrave.com. He is listed among his family at Monmouth Cemetery although there is no photograph of his headstone there, since the monument was erected over his body, which lies in Prairie Rose Cemetery in Republic County, most likely in a proper coffin.

There is also a note on Findagrave about one Gordon “Windbigler” being buried in a private cemetery 3.4 miles southeast of Republic, the site of his original interment. Despite everyone’s best intentions, Gordon’s bones remained there until 1923 when his brother, Dr. Clarence Winbigler from Harper, Kansas, arrived in Republic County to handle the matter himself.

By the way, when I googled Gordon Winbigler’s name looking for family details, the advertisement in the side panel on the genealogy site was for a haberdasher. I told you everybody knows about the hat.

* I later discovered evidence that he was indeed in Wyoming in 1901.