I have a confession to make. I haven’t been completely forthcoming about some of the photographs I’ve posted here. Some seem to beg for just a bit of polishing to make them more presentable. Somewhere in the process of developing, printing and scanning they’ve picked up specks of dust or miscellaneous stains, and I try to minimize those potential distractions and occasionally also bandage a few tattered corners.

Some of the photos posted recently had to be rotated a few degrees to plumb horizontal and vertical lines, to keep buildings and people from seeming as far off-balance as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Since I try not to interfere with the truth of a photograph, I would never perform this procedure on, say, a picture of the actual Leaning Tower of Pisa - or even one of a rickety farm building in imminent danger of tumbling down. However, for most subjects, keeping the horizon level and telephone poles pointing straight up, creates a more pleasing look.

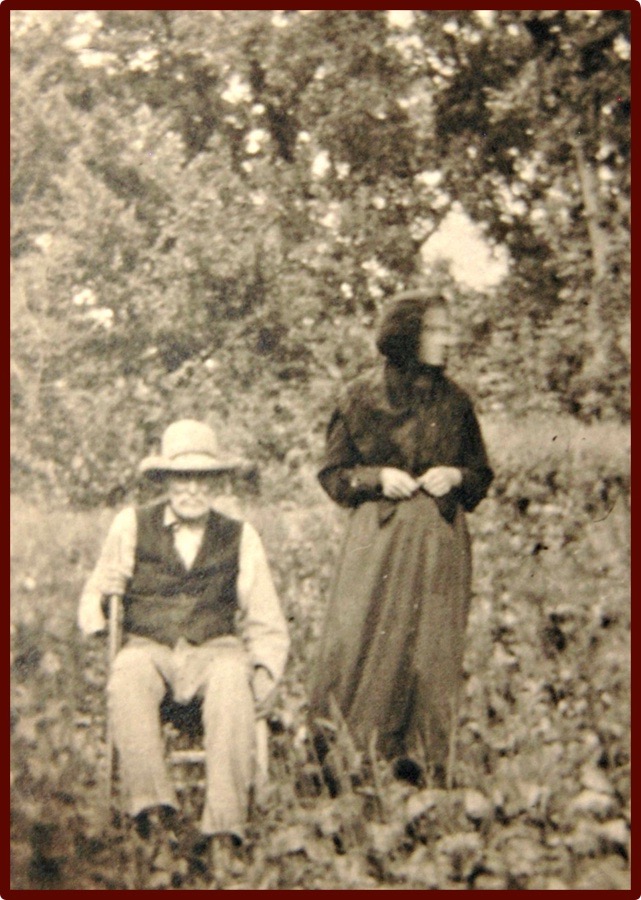

The one below, apparently showing Thomas and Orel Jane Lovewell pretending not to notice that their garden needs weeding, had to be dragged several degrees to square it up, and I think I know the reason why.

Subjects teetering one way or the other are especially evident in snapshots taken after the start of the 20th century, thanks in part to the popularity of the Kodak Brownie. The Brownie was a simple, cheap ($1) box camera which was cradled in the hands while held tightly against the stomach, with the photographer peering downward to keep the subject more or less centered in a tiny prismatic viewer, while pressing the shutter. Some instruction books recommended that the photographer should hold his breath at the crucial moment. While it was possible to hold the camera perfectly still and level while pushing a lever on the side of the box, it took some practice.

The picture at the left, like many shared here lately, was provided by Ashley Gresham and her mom, Dale Ann Johnson, descendants of Mary Lovewell and her husband, Ben Stofer.

When Ashley sent me a picture taken around 1934 of Mary and Ben posing with their grandchildren, I was surprised to note that in the 1930’s Ben dressed much the same way that my father did for most of his adult life. Fashions may have changed radically before then, but not so much since. Ben was a stock-buyer and realtor, while my dad worked in a bank after returning home from World War II. Born 43 years apart, nonetheless they were both mid-20th-century small-town businessmen, and evidently felt most comfortable wearing the business-casual attire of their day, slacks and a short-sleeved dress shirt, or a shirt with the sleeves rolled up.

Judging from the number of photos received the last few days, I have a feeling the two men had something else in common. Apparently, they both liked cameras quite a lot. In the last few years I’ve rediscovered my father’s own photo album, filled with pictures he took as wayfaring a teenager. We always had at least one camera around the house. When I was very very small, it was the ubiquitous Kodak Brownie Hawkeye molded of handsome black bakelite, a sturdy early-day plastic. It was difficult to take a picture with it that didn’t cut off the top of someone’s head. After a few years the Hawkeye was replaced by a Polaroid Highlander, an instant camera which produced very sharp black-and-white photographs that had to be coated with smelly goop to keep them from fading.

One of the first images Ben or Mary Stofer may have snapped with their vintage Brownie was the one above, of Mary’s parents in their back yard. The photographer in the family hadn’t yet perfected the art of holding the magic box upright (I fixed that), and Orel Jane apparently forgot to look away demurely until the very last instant.

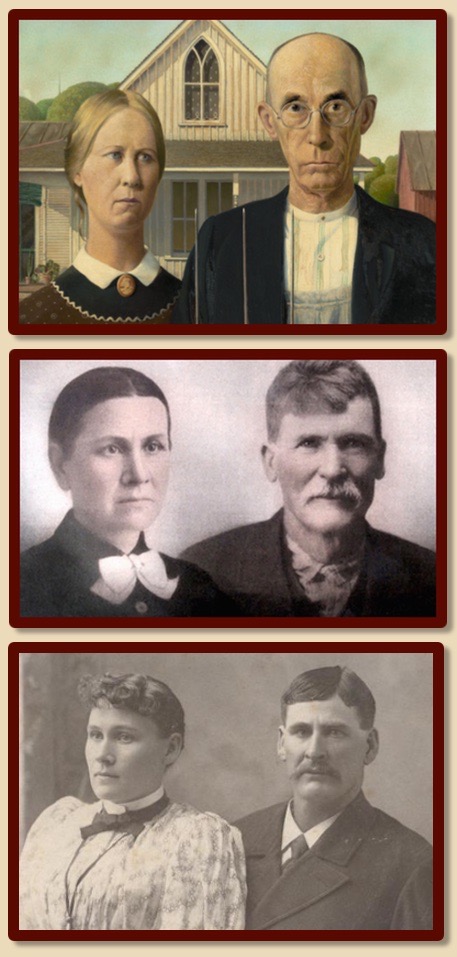

Did women of that era really think it was improper to gaze directly at the camera when posing with a man? Was staring straight into the eyes of the viewer supposed to be his job? Reflect for a moment on Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” top right, then at the photo of Juliana Robinson seated next to her father, Thomas Lovewell, and below it the one of Rhoda Robinson beside her brother John.

In the candid shot above it's interesting to see Thomas in a waistcoat. In nearly every other photo of him, he’s wearing a long coat over a checked shirt that’s buttoned all the way to the top, but without a tie. In this one the vest is fully buttoned but his shirtail has been left hanging out. I’ve been told that men in Thomas's day would not be caught posing next to a woman without wearing some sort of coat, because the shirt was considered an undergarment. A short-sleeved shirt and trousers? That would have seemed downright indecent.