If a picture is worth a thousand words, I’ve long ago used up my quota while writing about the “Pikes Peak or Bust” photograph, taken somewhere near Denver, probably late in 1859. However, it’s a complicated picture, encompassing at least three groups of people with various motives for congregating at the bottom of a hill in far-western Kansas Territory to share a smoke, perhaps wet their whistles with a few beers, and to get their picture taken. As I’ve written before, I suspect that the location is Daniel Chessman Oakes’ outdoor hospitality suite at Riley’s Gulch, in front of the tent he shared with his business partner, Abram “California Abe" Walrod. Oakes is said to have pitched his tent beside a millstream, and there does seem to be a small waterfall rushing down the right-hand side of the picture.

Phil Thornton, Thomas Lovewell’s great-great-grandson and a contributor to this site, emailed to ask if I had noticed that no one in the photograph seems to be toting a gun. It is one of the chief differences that set this picture apart from, say, stills from the old TV Western, “Wagon Train,” in which the only man not packing a sidearm is usually the bewhiskered cook. Oh, yes, the whiskers. The beard which Frank McGrath wore as Charlie Wooster set him apart from the rest of the cast - it marked him as an eccentric sidekick. Except for Ward Bond’s well-groomed mustache, the faces of the other regulars were clean-shaven. The real West seems to have been rather more hirsute.

Another discrepancy between the West of our collective imagination and the one captured on the photographic plate is the presence of mules. In most of the long-shots showing the train in motion, the beasts of burden on "Wagon Train” were horses, certainly more photogenic and probably easier to train than mules or oxen, but a terrible choice for hauling a wagon to California or Oregon. Those of us raised on a diet of TV Westerns might smile at the pervasive use of tobacco products in the photo, and the open bar. Most of the bottles displayed on the makeshift table probably contain nothing stronger than beer, but the ones that are half-empty may be half-full of something else. And is that a bucket of ice in front of Thomas? I suppose there’s coffee in the pot near Solomon Lovewell, ready to provide a libation for any teetotalers. The fact that it’s not a studio portrait means that “Pikes Peak or Bust” can be packed full of all sorts of small clues about daily life in the mining camps along Cherry Creek, and in the wagon trains that brought them there. My own favorite is the matching vests and ties worn by the wagon-master and his assistant. I’ll place a small bet that the vests were blue and the ties were bright yellow or goldenrod.

The group photograph has been used for years as a standard illustration for the Pikes Peak gold craze of 1859 and 1860, which was orchestrated to some degree by Daniel Chessman Oakes, who published a travel guide to the gold fields, and made sure western outfitting shops were stocked with copies. It seems ironic that a flaw in the plate has for many years concealed the identity of the most famous man in the photo, the one resting an arm across his elevated leg. Despite the distorted image, there’s no mistaking that dangling curlicue of hair atop the high forehead.

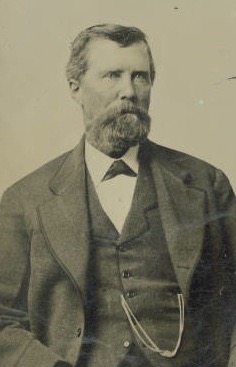

This photo on the left, showing guns at the ready, was taken in the 1880’s in Central City, Colorado. The man in the portrait is a legendary lawman named Richard Broad Williams, and the boy is his son Oscar, who followed the same career-path as his dad, before donating the "Pikes Peak or Bust" photograph to the Denver Public Library. It’s only logical to assume that the picture was in Oscar's possession in the first place because some of his relatives appear in it.

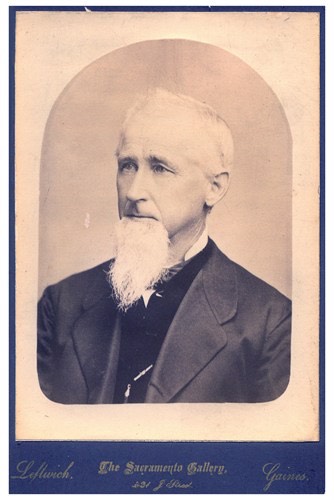

Oscar’s father Richard was only twelve when “Pikes Peak or Bust” was taken, and he had probably been left behind in Michigan. Richard Broad Williams was the son of John Henry Williams, an immigrant from Devonshire, England, who toiled in the mines of Michigan before moving to San Jose in the 1870’s. Pictures of him later in life show that John H. Williams had a slender face and a long, thin nose, the same facial features which mark the seated man who wears a large white hat, dark shirt and suspenders in the Pikes Peak photograph. Richard Broad Williams looked nothing like his father, but he did somewhat resemble the man with a bucket hat and a shoulder bag, who leans against the covered wagon while keeping a firm grip on a flask of liquor. This may be John Williams’ older brother Colin, visiting from Devonshire with their father, also named Colin, who could be the older bearded gentleman in a bucket hat and long coat.

Why were all of these men photographed together? There’s a chance that they traveled together. Oakes made several trips between western Iowa and the vicinity of Denver City in 1859, the last one in November, to haul a lumber mill to his campsite at Riley’s Gulch. If the photograph is a record of the arrival of the train they all traveled with, then we even know the name of the wagon-master, Alonzo Freas. It would be too much to hope that his assistant is Alfred Lovewell, working his way west by wrangling the mules. That would mean that we have a probable name for every man in the photograph.

But that still leaves the horses and the mules.