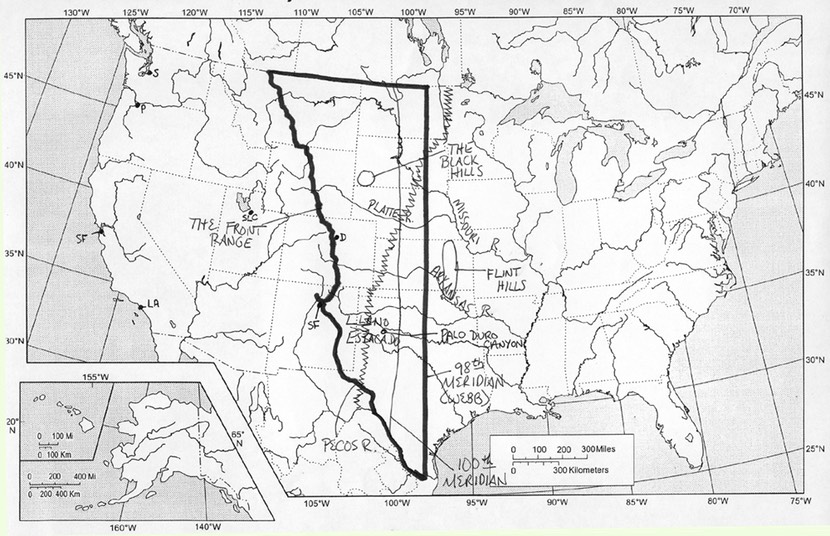

Some Kansas have long had a bone to pick with Washington Irving. He often gets the blame for applying the term “The Great American Desert” to at least the western third of the state, perhaps as much as the western half. Washington Irving didn’t invent the phrase, and he may have had the sand hills of Nebraska and South Dakota in mind when he used it to describe an area he likened to the steppes of Russia, peopled by wild tribes on horseback who reminded him of Tartars, in his book Astoria, first published in 1835. However, he certainly popularized the phrase, and maps soon began to pop up showing a huge swath of real estate tagged with that forbidding label, stretching from Canada to the southern tip of Texas.

Irving was a pioneer writer of American popular fiction before John Jacob Astor invited him to travel to the Pacific Northwest to write a history of the fur trade. His two best-known stories, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” appeared in 1819 in a volume called The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Recently, the Fox Network rolled the two tales together to make a sort of reboot of its old X-Files series, seasoned with a dash of Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and a pinch of those National Treasure movies.

Sleepy Hollow’s premiere episode opens with a Revolutionary War battle in which a beheaded Hessian trooper slices open a soldier in General Washington’s army named Ichabod Crane. Instead of dying, Crane is placed in a state of suspended animation by his supernaturally-empowered wife and merely slumbers, not for two decades, like Rip Van Winkle, but for over two centuries, awakening in the present day to join a small-town police force in battling evil in various forms.

Far-fetched even for what it is, the series is also quite a lot of fun, primarily because of the interplay between the lead actors, and Crane’s bemused reaction to the modern world, with its guns that fire more than once without reloading, and a fervent dedication to putting a Starbucks on every corner. The best moment for me was when Ichabod Crane, still clad in Colonial American garb, denounces his flip-phone as a piece of antiquated technology. In the midst of a diatribe against greedy telecommunications companies that cajole customers into continually upgrading their phones, he’s reminded that his partner has a newer model, and he wants one like hers.

I was moved to write a thumbnail review of the series only after learning that, besides the several Lovewell men who fought in and survived the Revolutionary War, there was at least one whose life it claimed: Ichabod Lovewell.

No, I’m not kidding. There was an Ichabod Lovewell, and he was injured in battle on July 7, 1777, dying on July 14. He had enlisted in Reed’s Regiment of Militia in 1775, but was serving in Colonel Alexander Scammell's Regiment (3d New Hampshire) when wounded, probably in the Battle of Hubbardton or its confused aftermath, during the withdrawal of American forces from Fort Ticonderoga. Ichabod must have been part of the rear guard commanded by Seth Warner, which had stopped for a breather at Hubbardton when General Simon Fraser’s redcoats attacked. The Americans were eventually scattered, but not before they put up a punishing fight that convinced the British not to try to pursue the main American army. The British and their allies lost half again as many men as the Americans. They did take a few hundred prisoners, apparently more than they could feed or effectively guard, for, as the first volume of New Hampshire’s Granite Monthly noted, "nearly all the prisoners, both officers and privates, resumed their old places or ranks…”

Besides the fact that he served at Bunker Hill, New Jersey and Ticonderoga before dying for his young country, we know very little about Ichabod Lovewell. He appears to have been a son of one of the Lovewell families from Dunstable, since he served alongside several of the local lads. He is also listed among members of Capt. William Walker’s company who suffered a loss of personal items at Bunker Hill on the 17th of June, 1775. When the Americans ran out of ammunition and were forced to retreat to Cambridge, Ichabod Lovewell had to leave behind one blanket, one shirt, one coat, one pair of hose, one pistol, and one fife. While the list does not directly inform us that Ichabod scrambled away from Bunker Hill clad in his shoes and underwear, it does suggest that he was musically inclined.

Map showing the extent of “The Great American Desert” is from the website legendsofkansas.com