I first came across a reference to Julian Changreau five or six years ago, when I was trying to determine what Thomas and Nancy Lovewell were doing in Marshall County, Kansas Territory in 1856. While leafing through Emma E. Forter’s* 1907 history of the county I read the sad tale, one which was evidently widely-reprinted with minimal variations, of the death by scourging of Changreau’s 15-year-old sister-in-law (See “Dark & Bloody Tales”). As far as I can tell, aside from the fact that he had a well-tended farm that he was very proud of, the story of an Indian maiden’s death contains most of the details anyone could recall about Julian Changreau. Of all the documents mentioning him, only one gives his first name. Every source I’ve reviewed lately refers to him simply as “Changreau.” I’m beginning to suspect that it was not his name.

According to Emma E. Forter, early-day settlers along the Black Vermillion seemed to regard him as having been one of two early and permanent fixtures of the valley: "On coming in the year 1855 to the valley of the Vermillion they found there Louis Tremble, a Frenchman, who had married a Sioux squaw, and who had been driven from the Rocky Mountains by an order of General Harney, expelling everyone of that nationality … Tremble had a neighbor, another Frenchman named Changreau whose wife was also a Sioux."

The general order expelling Tremble (Pronounced “Trom-blee”) and others of his heritage resulted from suspicion that French traders and their Native American wives were stirring up trouble between local tribes and a new wave of European migrants heading West. Changreau and Tremble continued to trade for furs in Nebraska, and then came to Kansas as the fur trade began to dry up. Indian villages no longer had to depend on middlemen such as Changreau and Tremble to provide them with guns and ammunition in exchange for robes and pelts. They could wait for the next distribution of annuity goods from the government and have them for nothing.

Although I first read the account of the death of the Sioux girl in Ms. Forter’s 1907 history, much of the story can be found almost verbatim in an 1890 supplement distributed with the Marysville True Republican, as well as in William Cutler’s “History of the State of Kansas,” published in 1883. Whatever form the story originally took, the fullest account of the incident uncovered so far, particularly valuable for its back-story involving Indian rivalry, is the one from the Marysville newspaper.

Louis Tremble, a half-breed, his wife, a full-blooded Sioux, and a Frenchman named Changreau, and his wife, a Sioux woman; her sister fifteen years old and several small children lived near the Vermillion before any white settlements were made there. Tremble built a toll bridge across the Vermillion. Changreau opened up a farm, raised vegetables and all kinds of produce, sold them at fabulous prices.

The country embracing all of northeastern Kansas was occupied by the Kaws, when in 1825, the government opened negotiations with them for the purchase of part of their territory. Between the Kaws and the Sioux, the parent tribes, there was an implacable hatred. The tribes frequently met and had war to the knife, and whoever was not killed, but captured, suffered death by torture in the most cruel manner.

When Changreau’s wife ran out to the field where he was working, with news that Kaws had ransacked their cabin and kidnapped her sister, he rode first to his neighbors’ cabins to enlist their help in rescuing the girl, and “… a few responded, among them was Hon. John D. Wells. They followed the trail for many hours, but becoming discouraged and fearing an ambush, they all turned back except the Frenchman, who pushed on alone. He followed the band until they camped on the Neosho river, near Council Grove."

In 1907, Emma E. Forter opted not to name revered Marshall County pioneer John D. Wells as a member of Changreau’s nervous band, and tried to put a positive spin on the decision of the Frenchman’s neighbors to turn around and go home. “Some of the neighbors joined him and followed the trail until they feared an ambush, when they decided they had best return to the defense of their own families.” Ms. Forter also tried to set the record straight about the scene of the crime: “Some historians state that this murder took place near Council Grove, but neighbors of the Changreau’s, who are still living, state positively that the murder of this young Indian maiden took place near where Irving now stands.”

In a previous blog entry on the subject, I raised the possibility that Thomas Lovewell and Daniel Davis may have arrived in Marshall County early enough to join Changreau’s posse, or at least could have learned about the killing first-hand from their neighbors, possibly even from Changreau himself. This guess is bolstered by a few snapshots of the neighborhood, tallies of eligible voters of Marshall County taken in 1857 and 1858, along with one more clue provided by Emma Forter. She says that soon after the kidnapping and murder, Changreau and Tremble moved their families away from the Vermillion valley.

In 1857 both of the former fur traders were still there. The Davis family was nowhere to be found, evidently having moved back to Iowa, acknowledging that this new territory was still “too wild.” Thomas Lovewell and his wife, along with an “L. Lovewell,” most likely Thomas's uncle Lyman, are listed among the residents at the bottom of page two of the census. At the top of the next page are “J. Shangrow” and “L. Tromelly,” phonetic spellings of the names of the two Frenchmen. The census reveals that one detail from all accounts about the Changreau family may be an exaggeration. Instead of “several small children,” the couple reported that only two were living at home in 1857 (Old-timers along the Vermillion may have confused the family with another former fur trader and his Sioux wife, the McCloskeys, who had five children).

The 1858 census-taker asked eligible voters how long ago they had arrived in Marshall County. Changreau said he settled there in 1853, Tremble in 1854. Thomas Lovewell reported that he and his wife Nancy arrived in May of 1856. According to the obituary of Thomas’s second wife, the former Orel Jane Davis, the Davis family also came to Kansas Territory in 1856, but stayed too short a time to leave evidence of their visit in the census. However, John Wells, the one neighbor named as a member of Changreau’s posse, was already there in 1855. The kidnapping and scourging could have happened that same year, although the continued presence of the two Frenchman until 1858 suggests a later date.

Irving, Kansas, eight or ten miles from Changreau’s cabin on the Vermillion, also seems a much more likely spot for the Kaws to have built a bonfire and conducted their bloodthirsty ceremony, torturing a despised Sioux enemy to death. Getting to the future site of Irving meant a ride of only a few hours, while Council Grove was two or three days distant. Considering what had happened there, and what would later happen, it seems odd that no legend ever attached itself to Irving about an Indian curse that appeared to dog the place almost from the start.

Founded in 1859, Irving had a slight connection with the American fur trade beyond being the spot where Julian Changreau discovered the body of his sister-in-law. It was named for New York author Washington Irving of “Sleepy Hollow” fame, who toured the prairies of Oklahoma and Kansas in the early 1830’s and in 1836 published “Astoria,” a history of a fur trading colony in the Northwest, written at the urging of his friend John Jacob Astor. The new village of Irving in Marshall County suffered from drought through all of 1860 and was clobbered that fall by a windstorm which blew down buildings, took the roofs from cabins and damaged the mill. Grasshoppers invaded in 1866 and again in 1875. There was a flood in 1903 and plans for the Tuttle Creek Reservoir later left it a ghost town. But Irving's most famous calamity happened on May 30, 1879, a day for the record books, when separate storm systems produced two tornadoes that hit it with a one-two punch, destroying most of the town and killing 19 residents. The catastrophe brought photographers to the site to set up their cumbersome stereographic cameras, and was reported in the national press.

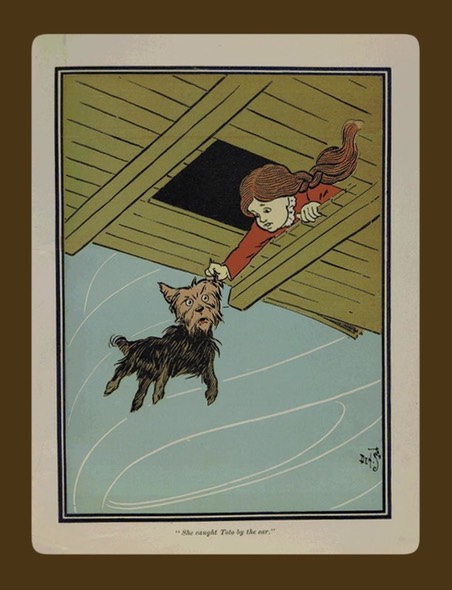

Another New York writer, one with a background in theatre and a fondness for children, may have been especially touched by a newspaper account of the deaths of six members of the Gale family at Irving, including thirteen-year-old Dorothy.**

Deciding that little girls should not be shattered by Kansas twisters and left face-down in the mud, L. Frank Baum instead whisked away his Dorothy Gale from Kansas to the Emerald City, where he could keep her safe forever.

Illustration from 1900 edition “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” from the Library of Congress

* In my original posting I called the author “Emma E. Porter,” which is how her name appears in the electronic transcription of “The History of Marshall County, Kansas” which I’ve been consulting for years. Unfortunately the OCR software’s eyesight is no better than my own. If I had downloaded a different transcription of Emma Forter’s book, I might have called her “Emma E. Foster.” The lady’s name was Forter, which is evident if you take a magnifying glass to her portrait at the top of the page.

** Marshall County resident Keith Jones assures me that no member of the Gale family died in the May 1879 storms at Irving. Although the Gale (or Gail) residence was badly damaged and every member of the family, including a baby and a small child, was flung through the air a distance ranging from 50 to 150 yards, all apparently landed without serious injury. See my later postings “Gail-Force Winds,” and “Seeing Nellie Home” for a more truthful version of the story. For a surprising connection between survivors of the Irving tornado and Republic County history, see “Happiness While You Wait."